According to Sifted, former Northvolt CEO Peter Carlsson and colleague Siddharth Khullar have officially launched Aris Machina after raising a $10.7 million pre-seed round back in May. The funding was led by Earlybird with participation from Village Global, Ainu, Planet A, and Peter Thiel-backed Snö. The startup aims to build an “agentic operating system” that coordinates factory machines, data streams, and legacy tools into something intelligent. Aris Machina has already hired 17 people, mostly from bankrupt Northvolt, and built two initial applications focused on battery production. The company tested its products extensively using data from an unnamed facility to verify the system works in production conditions.

The Northvolt ghost in the machine

Here’s the thing that’s hard to ignore: this team comes directly from Northvolt, which filed for bankruptcy in March. Now, failure isn’t necessarily a bad thing – Khullar himself says “we’ve failed enough times” and calls their experience “battle scars.” But let’s be real: building factory software with a team from a company that couldn’t keep its own factories running? That’s gonna raise some eyebrows.

And the timing is… interesting. These folks were “all looking for jobs” after Northvolt’s collapse, and suddenly there’s $10.7 million to reassemble the dream team. It’s either brilliant opportunism or concerningly familiar. I mean, they’re starting with battery production again – the exact same industry where their previous venture failed. That takes either incredible confidence or willful ignorance of pattern recognition.

The manufacturing mess they’re tackling

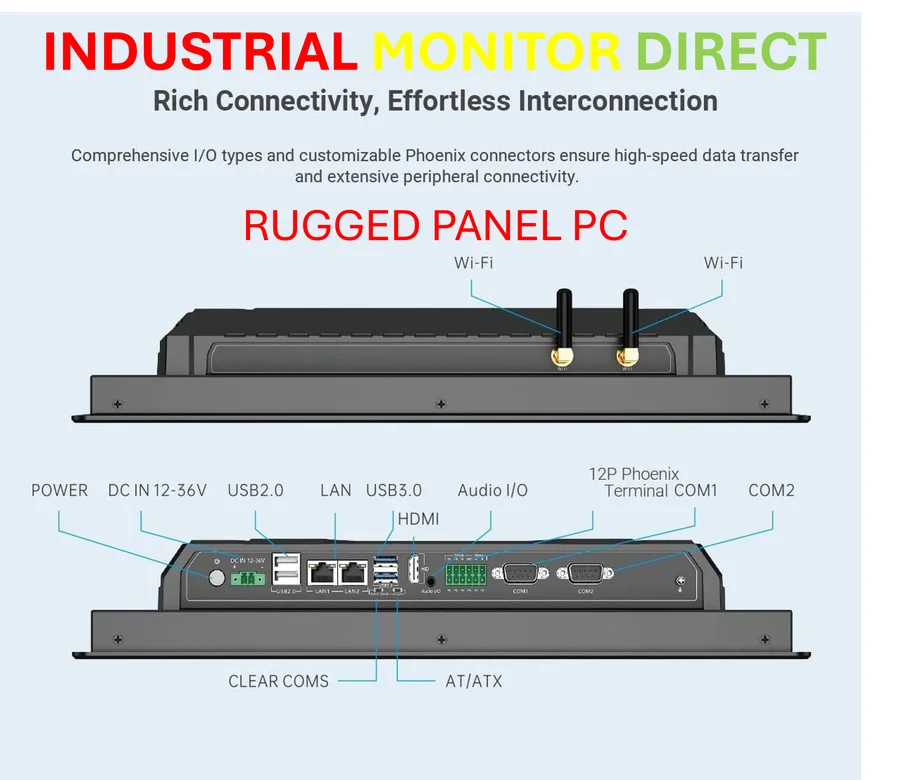

Look, the problem they’re solving is absolutely real. Khullar describes factory floors with 1 million events per hour on a single line, 130+ tools that don’t talk to each other, and requiring the original researcher to troubleshoot problems. That’s basically organized chaos. And when you’re dealing with industrial systems that need reliable industrial panel PCs and hardware that can withstand factory conditions, the stakes are high.

Their approach of combining statistics with LLMs to achieve repeatability makes sense. Khullar cites that brutal MIT report finding 95% of corporate genAI pilots don’t deliver measurable business value. Non-repeatability is exactly why most AI projects in manufacturing fail – you can’t have your quality control system giving different answers on Tuesday than it did on Monday.

The billion-dollar scale question

So they’re starting with batteries but want to go sector-agnostic across semiconductors, aerospace, defense, biopharma… basically anything involving physics and chemistry. That’s either visionary or delusional. Manufacturing isn’t some monolithic industry – the difference between making battery cells and producing pharmaceuticals is enormous.

And building a true “operating system” for factories? That’s the holy grail that countless companies have attempted. Siemens, Rockwell, countless startups – they’ve all tried to own the factory floor software stack. It’s not just about connecting machines; it’s about understanding decades of tribal knowledge, legacy systems, and industry-specific workflows.

The execution reality check

Khullar says they “raised money not to sit around for three years and slowly trickle along.” Good, because they can’t afford to. $10.7 million sounds like a lot for a pre-seed, but in manufacturing tech? That’s pocket change when you’re talking about building robust industrial software that can’t fail when millions of dollars of equipment is on the line.

The fact they’ve already built two applications and tested on real facility data is promising. Turning months of integration work into approximately one week per machine? If they can actually deliver that, it’s transformative. But manufacturing is littered with the corpses of startups that had great demos but couldn’t handle the messy reality of factory floors.

Basically, this could either be the foundation of the next great industrial software company or another cautionary tale about how hard it is to tame manufacturing complexity. The team has the experience and the funding – now we’ll see if they can actually deliver where so many others have failed.