According to SciTechDaily, a research team led by Professor Jaeyeong Heo and Dr. Rahul Kumar Yadav from Chonnam National University in South Korea has solved a major problem with tin monosulfide (SnS) solar cells. They did it by inserting an incredibly thin, 7-nanometer layer of germanium oxide (GeO) between the cell’s absorber layer and its metal back contact. This tiny interlayer fixed multiple issues at the problematic rear interface, which suppressed defects, blocked unwanted chemical reactions, and improved charge collection. The result was a dramatic efficiency jump, pushing the power conversion efficiency of their vapor-deposited SnS solar cells from 3.71% to 4.81%. That’s a nearly 30% relative increase and marks one of the highest efficiencies reported for this type of cell.

Why this is a big deal

Look, thin-film solar has been the “next big thing” for a while, promising cheaper, lighter, and more flexible panels than traditional silicon. Materials like tin sulfide (SnS) are especially attractive because they’re made from abundant, non-toxic elements—no rare indium or gallium required. But here’s the thing: for years, the real-world performance of SnS cells has been stuck way below what physics says should be possible. The main villain? A messy, lossy interface where the semiconductor meets the metal contact. This paper basically shows that you don’t need to reinvent the whole cell; you just need to engineer that one critical junction with atomic precision. It’s a classic case of a materials science interface problem holding back an entire technology.

Broader implications beyond solar

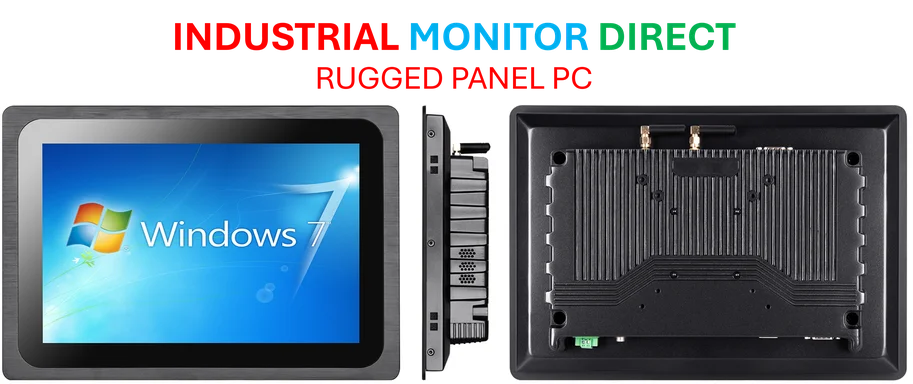

This isn’t just a solar story. The researchers point out that mastering the metal/semiconductor interface is a universal challenge in electronics. Think about it: the same principles affect the contact resistance in thin-film transistors, the sensitivity of sensors, the efficiency of thermoelectric devices, and even the stability of flexible electronics. Solving an interface problem in one area often provides a blueprint for others. For industries relying on precise, reliable thin-film devices—from advanced manufacturing to industrial panel PCs where display durability and performance are critical—these kinds of foundational advances in material stability and contact engineering are what enable the next generation of robust hardware. It’s a reminder that sometimes the smallest layers have the biggest impact.

What comes next

So, is tin sulfide solar ready for your rooftop? Not quite. An efficiency of 4.81% is a huge leap for this specific material, but it’s still far behind the ~25% of commercial silicon panels. The real significance is proving that the performance gap isn’t fundamental; it’s an engineering puzzle that can be solved. The method they used—oxidizing a thin germanium film during a vapor deposition process—is also promising because it’s scalable and compatible with existing thin-film manufacturing. Now the question is: can this interface strategy be combined with other improvements to push SnS cells into a truly competitive range? This work, detailed in the journal Small, opens a clear new pathway to try. It turns a stubborn roadblock into a design feature.